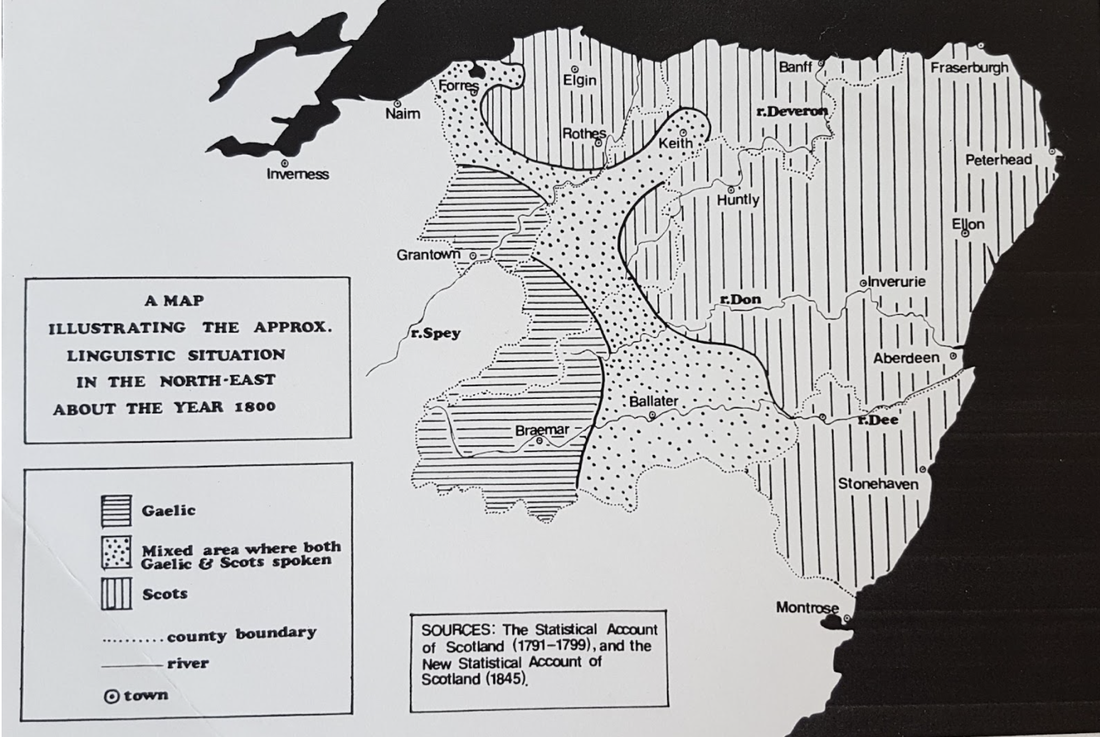

Opening this show really illuminated my own process to me. Opening this show really illuminated my own process to me. The curators explored aspects of Le Guins approach which influenced the show and their thinking, and discussed her 1986 essay “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction” from the book “Dancing at the Edge of the World” (Grove Press, 1989). In “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”, Ursula Le Guin reiterates the idea that the first tool, rather than being a weapon, was probably a vessel or bag for gathering. This “carrier bag theory” has two key hypothesis: it positions women as the earliest creators of tools, and the novel as a vessel for stories which can move beyond a hero narrative. My process for creating new work tends to begin with gathering a whole range of material- poems, archive recordings, images, sounds, instruments, children’s rhymes, melodies and pieces of the landscape itself. Shells, bones, plants, ceramics. This is not so much a considered process but a kind of crashing through my natural encounters with the folk tradition and the context it sits in, and seeing what sticks. Le Guins essay helped me see this in the context of a wider approach to creating narratives and stories. “If it is a human thing to do to put something you want, because it's useful, edible, or beautiful, into a bag, or a basket, or a bit of rolled bark or leaf, or a net woven of your own hair, or what have you, and then take it home with you, home being another, larger kind of pouch or bag, a container for people, and then later on you take it out and eat it or share it or store it up for winter in a solider container or put it in the medicine bundle or the shrine or the museum, the holy place, the area that contains what is sacred, and then the next day you probably do much the same again—if to do that is human, if that's what it takes, then I am a human being after all. Fully, freely, gladly, for the first time....” Does it not describe perfectly the process of gathering, creating, recording, performing, sharing and saving that is inherent to the development of a repertoire of song? Hearing, hearing again, finding, practising, reiterating, choosing the colours, shifting, recombining but ultimately bringing together. Before setting out to achieve anything in particular, before i was performing, I developed a repertoire of stories sung from women’s perspectives. Once I started sharing this work the focus became the foundational space that women occupy in the Scots song tradition. Quinie is NE scots word meaning a quine-stane, is a cornerstone- a foundational stone of a building, as well as a woman. Le Guins essay articulates why I was drawn to song to do this - how the singers process of gathering and holding creates a net where different kinds of narratives can be. “It's clear that the Hero does not look well in this bag. He needs a stage or a pedestal, or a pinnacle. You put him in a bag and he looks like a rabbit, like a potato.” Performing at DCA, December 2019. Photo by Erika Stevenson Filling my bag I began gathering from my usual standpoint- archival recordings of my regular muse Lizzie Higgins (1929-1993). Lizzie was born in Aberdeen, and was a Scottish Gyspy Traveller. She working as a fish-filleter before coming to public attention as a singer at the age of 38, and unfortunately died only twenty-six years later. I could talk about Lizzie’s story all day but I won’t. There is loads more information about her life availible here. Lizzie’s voice is striking in its ability to communicate meaning through shape, tone, texture and volume. She was an interesting figure in the folk revival, as someone who embodies a kind of inbetween space between ‘authentic’ tradition bearer and revival performer. She was quite determined to articulate her USP as distinct from her mother, Jeannie Robertson, who was a famous traditional singer. Part of her articulation of the difference was based on Lizzie having learnt her singing technique and repertoire from her father- who was an accomplished piper. Lizzie’s ‘piping sangs’ are for me where her magic lies- the modal melodies, ornamentation and boldness. Her relationship with her own process, and her social policing of her own talent, seemed to echo larger patterns in the traditional music world that I want to interrogate and disrupt with my work. Beginning in the School of Scottish studies archives, I reviewed recordings and writing about Lizzie from 1970s and 80s. Some of these I had heard before- particularly recordings by Stephanie Smith and Hamish Henderson. In recordings of interviews with her, she talks about her thoughts on diddling and pipe mouth music. Diddling is the practice of singing a tune with non-lexical vocables instead of words, often to a fast rhythm used for dancing. Diddling comes in a variety of forms, with some linked to specific instruments such as bagpipes or fiddle, and others used as a standalone vocal performance (Chambers 1980: 17-24). Lizzie was a very good diddler- and she used diddling as a process to put together new tunes with songs. However she would never have performed diddling onstage. In fact she clarifies that her father forbade her from piping and pipe-diddling, in spite of her prodigious talent at the chanter (see Chambers 1980: 21-36). The establishment of diddling contests and the romanticism of the folk revival shifted diddling from being predominantly female discipline, performed in informal, domestic or care giving spaces to a predominantly male one. In this new realm, dominated by ideas prestige and a white male-normative model, women were structurally discouraged from joining in even if they were theoretically ‘allowed’ to contribute. The folk revival, obsessed with ideas of authenticity and nostalgic ideas of rurality, acted as a lens through which we now view folk cultures of Scotland. Alongside the divisions along gender lines, hierarchies were held up across ethnicities in pipe related mouth music. With canntaireachd held up as the ‘true’ translation of pipe music used for the purpose of transmission ‘cantering’ or ‘diddling’ was used to describe the vocal transcription process for non-pipers or informally trained pipers (e.g. Scottish Travellers). If you are interested in listening to some examples, Mary Morrison is a gaelic singer who has a wonderful example of canntaireachd in her rendition of the pibroch piece A Cholla Mo Rùn. Following on from this line of enquiry, I am now gathering melodies and examples of piping mouth music from across the archives and other sources looking at how I can expand my understanding of the capacity of my voice to imitate the pipes. In addition to the gathering of melody, I am also looking for inspiration and concepts for the lyrics of the songs. The thing that has always brought my music together is that it is an expression of an imagined landscape. When I am singing these songs I am feeling a place. They are an amalgamation of feelings of places. I’m often drawn to poetry and pieces of scots writing that expand on this or ‘zoom in’ on particular aspects of place (objects / animals / plants / particular sites / homes). “Language and its creative expression through song and story encodes human memory and experience. Songs are honed to the rhythms and patterns of speech which are connected to the land itself. Together they form a cultural ecology which passes on knowledge of flora and fauna, geological forms, seasonality.” Mairi McFadyen A map Illustrating the approximate linguistic situation in the north-east in the year 1800

Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWritings, reflections and an archive of research from Quinie (Josie Vallely). Archives

February 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed