|

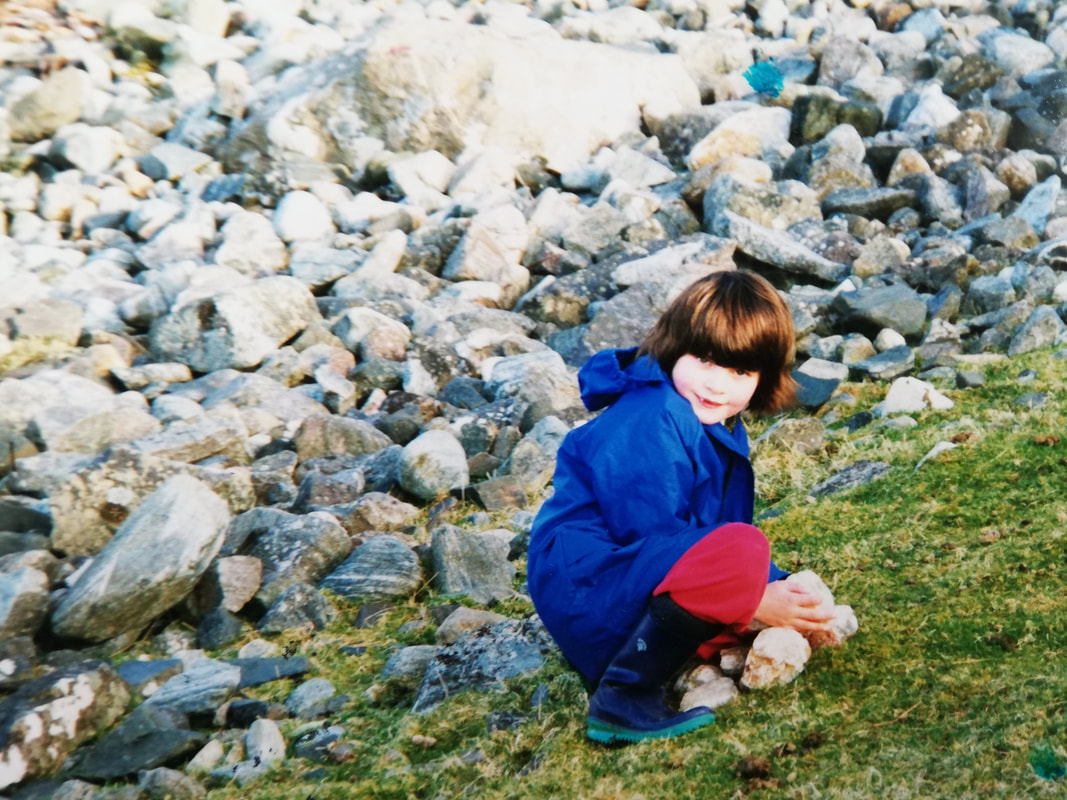

My experience of being on residency in Australia was, at the time, quite disorientating. It felt unclear to me what I was meant to be doing and how this place that was so similar but also so different would inform my practice. Naturally, I was drawn to the environment around me and the different sounds and nature that I could orientate to. A number of the artists that we were working with were also working with these natural sounds and spaces, through field recording improvisation and poetry. But ultimately, it wasn't the direct gathering of the sounds that I was interested in for my practice. I found myself more interested in gathering physical objects. This is something I have always done since I was a child, compulsively stuffing my pockets with shells and nuts and rocks and live animals (unharmed).

Back in the group in Fremantle Art Center, I mentioned this to the artists I was working with. It turned out that this wasn’t seen as a great idea in this new context I was in. Different relationships to 'country' and the idea that we must respect it in a different kind of way means that removing things, especially as someone who isn’t indigenous to the land, only echoes the violence that has been done upon this landscape and its people. It took me a while to get my head around this because I feel like in Scotland it almost works the other way. Here, as the common person, you aggressively assert your right to access the landscape, cultivate it, and know it. This is part of a rejection of ownership of land and restrictions of use. But it did make me think more about the indigenous practices we have here and how by overconsumption and collection, we risk destroying cultural practices alongside the 'nature'.

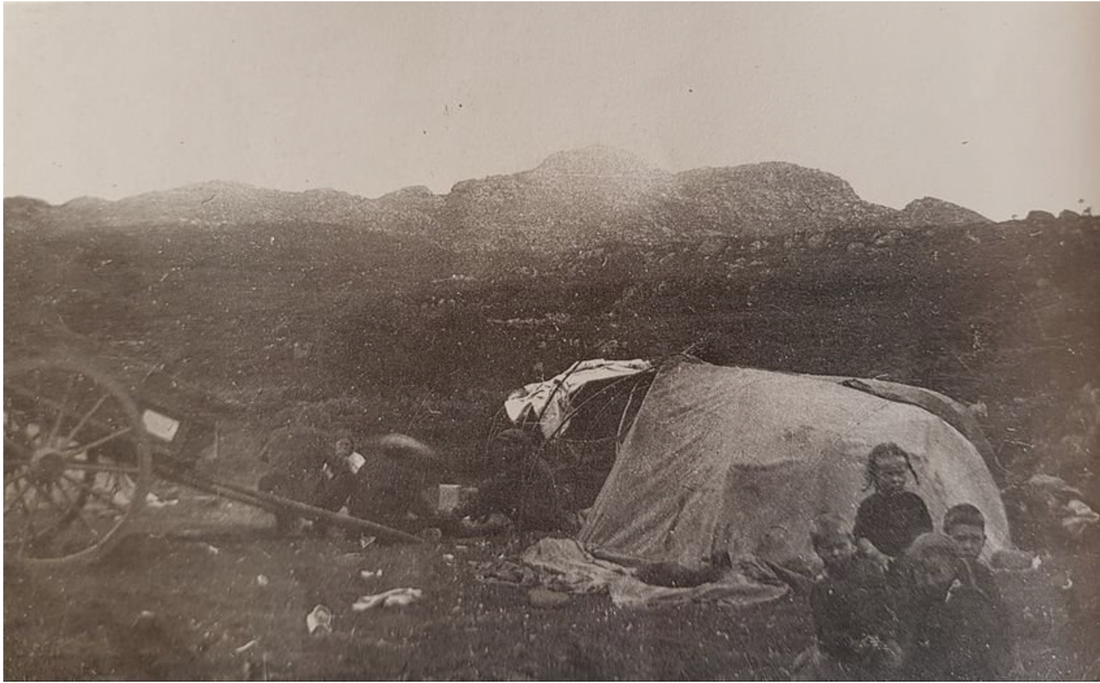

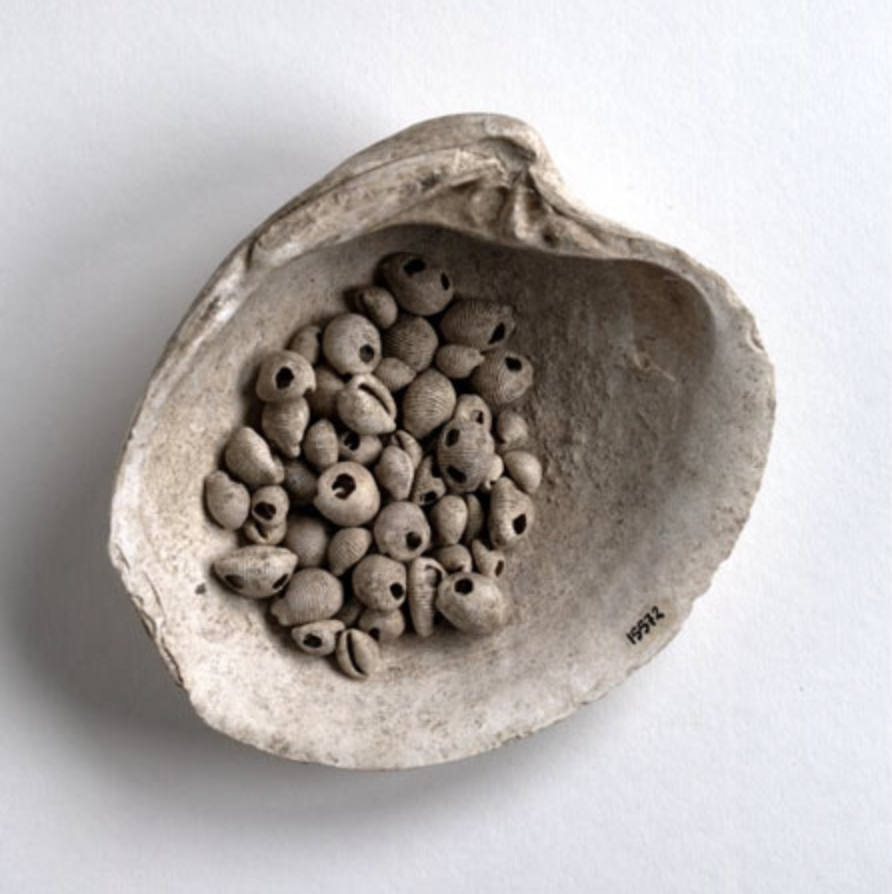

For example, it made me think a lot about the collection of freshwater mussel pearls by Scottish Traveller people. Freshwater mussels in Scotland are critically endangered, and it's incredibly important that they are protected and preserved. However, they were collected by Scottish Traveller people for centuries. They are beautiful pearls that can be seen in some of our oldest jewellery. Now incredibly rare and in need of legal protection, I see a kind of duel tragedy where both the mussels and the indigenous guardians of them have suffered from their habitat loss, life cycle disruption and overconsumption. If you are interested in this take then i recommend reading 'Last summer pearls', an excerpt from 'Late Light' by Michael Malay which describes how the disappearance of freshwater pearl mussels from Scottish rivers is mirrored by the disappearance of the 'summer walkers', Gaelic-speaking travellers and mussel-fishers living a semi-nomadic lifestyle into the modern age.

You could also have a read of this article where Willie MacRae, who’s family have farmed Kerrysdale since 1936, tells us about the families and camps he remembers from his childhood in the 1950s and 60s.

"As well as having open fields which were good for grazing horses, Kerrysdale also had the River Kerry and it’s pearl mussels, which at the time weren’t protected. One family, the Davies from east Sutherland, were expert pearl fishers who fished the Oykel in Sutherland too, and they were good at fishing the pearls in a sustainable way. This would usually be in summer, when it was more pleasant to stand in the river all day. The Travellers would bring a long wooden fishing pole with them, and a metal box with a glass bottom which would be pushed into the water and used to see the riverbed. Someone in the late 40s or early 50s found a pearl with a value of £50, which today would be worth thousands of pounds. And if they found pearls that were immature and still brown, or misshaped and of little value, they’d give them to the MacRae children. Any pearls thought to be of value would be taken to Dingwall or Inverness to be valued."

My solution in Australia for this compulsive collecting urge that I had was to begin capturing the things I wish to collect and shoot little portraits of them. This really helped me get a better understanding of the things that I was drawn to and also freed me up to start collecting things that practically I wouldn't have been able to take home anyway. I made these portraits into this short film.

I spoke to fellow residency artist Theresa, who is Pakana, an indigenous Tasmanian artist, and she was telling me all about their tradition of shell stringing. Shell stringing is the cultural practice of collecting, preparing, and stringing shells to make necklaces and bracelets by Tasmanian Aboriginal women. This knowledge is passed from mothers and grandmothers to their daughters and granddaughters and maintains an important link between traditional and contemporary Aboriginal life. Again, this echoes the plight of this freshwater mussel that I was talking about, because the shells that are traditionally used have become endangered. However, some of the elders in the community have been given special rights to continue collecting them to keep the traditional alive.

For Pakana an intimate understanding of Sea Country and the skill of collecting and stringing shells extends far beyond living memory. Pierced shells from Tasmania’s west coast have dated the tradition to at least 1800 years ago. Shell stringing is the Community’s longest continued cultural practice, a practice which not only withstood invasion but continued throughout the Black War and during the time Pakana Ancestors were incarcerated in government missions at Wybalenna on Flinders Island and Oyster Cove, south of Hobart. I found it so interesting the way that this ancient craft of stringing shells directly linked Theresa back to her ancestors and her culture. Recently, I was reading about pierced Cowrie (or groatie buckies) shells found off the coast of Argyle, from at least 5 thousand years ago. These beads must have been a necklace, or jewellery of some sort. What is my relationship to the people that made that necklace? I think I have been brought up to see the people of the past as an entirely different species from me, a kind of clunky humanish animal that roamed around making the most of what they had. But I have always known that these are the most prised of the shells on the beach- I have spent many hours lying flat, cold damp coming through my jumper, propped up on my elbows, looking for them. Did someone tell me that they where? Why do i like them so much? Why did they like them so much? If nothing, me and my distant ancestors have taste in shells in common.

My time spent in Australia opened up to me another way of thinking about the people of the past. It also demonstrated to me that honoring these traditions is not about abandoning life as we have it now. It's not about pretending that we live in bow tents made of skins, eating limpets. Theresa wore her beautifully beaded shell bracelet on a hand of equally beautiful, and very glamorous nails. She helped me understand that honoring craft and culture is not always about going backwards in time.

Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWritings, reflections and an archive of research from Quinie (Josie Vallely). Archives

February 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed