|

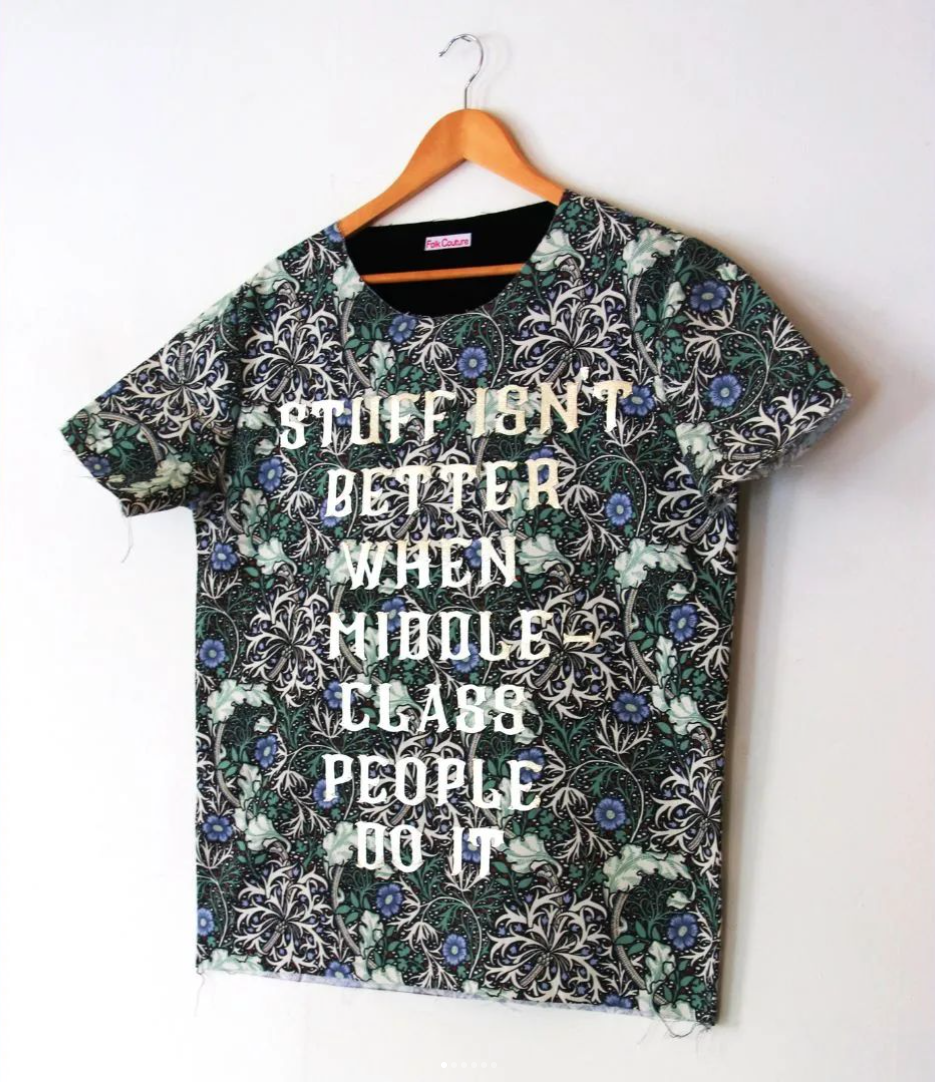

I work with a lot of song material that comes from the Scottish Traveller tradition, I'm keen to explore what that means to be playing and learning within these ‘folk’ traditions that aren't necessarily mine. I became aware of the ‘Folk is a Feminist Issue’ project by Lucy Wright. Her vision is of a new, more inclusive and far-reaching definition of folk that celebrates and empowers everybody, starting with women. To Lucy, this is a crucial step for folk to be recognised as the powerhouse that it is, not just as a musical genre, but as an agent for resistance and change in the arts and culture. I spoke to Lucy about her work and some of the themes we are interested in, this conversation was recorded in 2022 as part of the Ghost Tunes project. Where I have come to with my own practice, is that while there are problems with the way that folk works, and there are complications in how tradition is discussed and dealt with, there is also value in engaging with it. It's not like we want to just say it's totally out of bounds, or put in hard and fast rules about who's allowed to engage with things and who isn't, who a song belongs to and who it doesn't belong to. It's tricky, isn't it? I sort of touch on it in the manifesta..one of the points is about not appropriating other people's folk. And I think there's a fine line between admiring something—being excited about it and wanting to share it, maybe even wanting to learn it for yourself, if that’s appropriate— and, you know, claiming it as your own. There’s examples where outsiders have become the most visible spokespeople for a practice whose community remains very marginalised and that seems wrong to me. If we’re coming in from the outside—especially if we belong to a dominant group—our job is to hold the space for the people who are currently kept out of the spheres of power and influence. We need to be allies not colonisers. I'm not saying that there aren’t ways for ‘outsiders’ to take part in and share culture that is not part of their own heritage or background—that’s part of the way that cultures evolve—but it needs to be approached carefully and informedly. I think it's like academic citations…at the very, very least, you need to acknowledge your source and ideally state honestly what your relationship to that material is. What bothers me most is where middle-class, white, (usually) men use narratives of ‘salvage’ and ‘protection’ to describe their co-option of the cultural practices of marginalised communities as if they have somehow personally rescued them. I find that pretty insulting and erasing of those people who are already doing that work at a community level. A lot of my past work has been with girls’ carnival morris dancing which is form of morris that's unique to the Northwest of England and practised almost exclusively by working-class girls and women. It's been excluded from the histories of morris dancing in England for years, largely because it doesn’t fit the image a lot of people want to have of ‘folk’. Girls’ morris has very much evolved outside of a ‘folk’ aesthetic and you wouldn’t find it at a folk festival or other folk revival event. The performers dance to pop music, they wear sequinned dresses and use pom-poms (called ‘shakers’) similar to cheerleaders: it's absolutely fantastic, a real feat of synchronicity and ingenuity and I love it so much! But it's not my tradition. If I had grown up in the northwest, I might have done it as my background is similar, but I grew up elsewhere, and so it doesn't belong to me. I've written some of the only research about girls’ morris and I've always felt like that’s a huge responsibility. I don't want to be the only voice on it. So I've tried very hard to come up with ways to share that knowledge and that research in ways that are co-created with the community, rather than it just being me speaking on their behalf. So I can understand the kind of tension that you feel coming from outside of a community. I think it's very possible to negotiate, but it needs continual adjustment and self-reflection. The important thing is to be aware of the issues and look for ways to raise others up, rather than appropriate from them. One trend I have observed that continues in contemporary and mainstream folk industry is a replication of colonial attitudes of discovery and preservation that we see all the time in relation to marginalised communities. There are contemporary ‘folk’ musicians making a living from other people and other culture’s work without recognising the colonial aspect of their actions. I have heard first hand of contemporary song collectors not keeping their commitments to communities and taking advantage of singers for their own career gains, taking personal contacts and damaging relationships with Traveller communities. It’s not on and I am very happy to speak out against people doing that kind of work. I think it can be very Othering. There is that persistent, but flawed concept of ‘folk’ being about the culture of ‘primitive people’, ‘unlettered’ or illiterate people—people who are outside of regular society, whatever that means, and I just don't think that exists, and I don't think it ever really did exist. Even in the 19th century, people were always moving around and coming into contact with different cultural practices, so the idea that there were ever these totally isolated communities who might hold the key to an ‘essential’ national culture…well that’s been roundly debunked in scholarship for years. When I first set out to find contemporary folk practices I was told repeatedly that there was ‘nothing left to collect’, but that was because people were working from those old assumptions about who ‘the folk’ are. I’ve found lots of great performances and customs that, for me, bear all the hallmarks of ‘folk’—as in, self-organised and self-determining culture—but which don’t form part of the established canon. For me, ‘folk’ isn’t a designator of a particular, heavily romanticised community. Instead it describes a way of approaching culture—the way we create our own entertainment and our own art and politics—that’s open to, and inevitably applies to, everyone. Whether you're part of the dominant class or not, everybody will take part in some kind of folk culture. And to separate it out, to limit it to a specific musical genre is to deny its wider application and power. Yeah, totally. I see time and time again a repeat of what has always happened - an academic middle class going in and selecting what they saw to be the important traditions. It's not like people are being encouraged to go and collect people's Adele covers, you know. And that's always happened. The singers that I love, like Lizzie Higgins who's a Scottish traveller, she sang incredible traditional songs, but she loved singing Elvis and contemporary music, but no-one ever recorded her Elvis covers, which is a great loss - I bet they were amazing. Yeah, absolutely. People often have a very firm idea in mind of what ‘folk’ is. That means that when they encounter something that doesn’t look like they have been led to expect, that practice is often ignored, or changed or left out—and that’s sort of how the present canon of ‘folk arts’ was created. It’s one of the myths of ethnographic research that collecting is some sort of objective activity, and that the person doing the research and doing the collecting doesn't bring a whole host of their own preconceptions and ideas and framings, but we all do that, unavoidably. Prior to the ‘crisis of representation’ in the humanities during the 1980s, that was not very well spoken about, but things have moved on since then. However, the canon of folk music and dance still hasn’t been updated to reflect that. At the same time, for all its appeals to being the music of the ‘ordinary’ working man and woman in history, the contemporary folk as an industry continues to be (primarily) the domain of the rather privileged, with an accompanying tendency to vilify or mock the working class culture of the present day. I see this all the time with girls’ morris dancing, which is still rather looked down upon—if it’s recognised at all—while ‘reinventions’ of morris by middle-class people are widely celebrated. I always want to shout, ‘girls’ morris also redefines what ‘folk’ looks like!’ but for some reason it is never felt to count. The posh boys and girls are still regarded as the main spokespeople—and the saviours—of folk. It was ever thus, of course, but I SO want to move away from that. Yeah. I think one of the things that happens in Scottish culture is that because traveller songs, music and stories were collected so long ago, and then ‘re-packaged’ during the folk revival. They've kind of become cemented as Scottish traditions, not as Traveller traditions. And I think that then has led to a bit of confusion about who they belong to. And it's also meant that they have been swept up in this national project of tartan and shortbread tins. And that really, I think, is quite a scary thing when you realise how marginalised and discriminated against these communities are in Scotland and that as a nation, we're not willing to commit to providing basic rights for Traveller communities. But we do want to take what serves us from them. There are so many instances throughout history—and in the present day—where the culture of marginalised communities is highly valued—popularised and often heavily monetised—but this fails to benefit the people who originated it. I’m thinking right now of ‘blackfishing’ where certain cultural practices are highly stigmatised when they’re embodied by black people, but can offer cache and ‘cool’ to white people who appropriate them. I think that happens with working-class culture too. Darren Garvey speaks of it as a ‘poverty safari’... The arts draws very heavily on working-class culture, but actually, working-class people are massively underrepresented in the arts. And things are getting worse, not better. On a personal level, as an artist and a researcher, I am really fascinated by what people do, by other people's cultures. But I'm also acutely aware of how easy it is to overstep the mark, or just get it wrong. I find it really frustrating when people talk about how they have ‘discovered’ something because it’s so important to remember that just because something is new to you does not mean it's new to the world, not least the people who are already practising it. It’s like ‘main character syndrome’ played out across culture and theory! I feel as though I see a lot of art, which is very inspired by a perceived aesthetic of what folk is, and it's almost always quirky and quaint and weird and rustic and pastoral or creepy Gothic. I get that these things are kind of fun and seductive, but folk can also be mundane and ugly and urban…it’s not always (or even very often) aesthetic and mystical! Every now and again folk gets a tiny bit fashionable and then a whole bunch of people start making stuff about it. And probably next week, they'll do it about something else. Something that I really admire is when I see an artist or a musician or performer of any kind, who has really spent some time really thinking about ‘folk’—what it meant historically and what it means today. And then being really clear about their positionality on that. You know, is what you’re doing part of the problem, or are you challenging the status quo? I agree that knowledge of a tradition and a grounding of the systems that they are within is essential. But I’m wary of that then leading to performative displays of that knowledge - like badges of authenticity. What is authenticity in a performance of folk? Is it necessary? When I first started singing ballads, and was learning about this world of song, which I find really fascinating and rich, I was initially really drawn to the like catalogues of song. This idea that if you knew enough about that, then you would be more authentic. And if you could quote The Roud number or whatever it was, of a ballad, and know its lineage, then maybe you would be accepted into the social scene of whatever was going on. That was something that was really encouraged in the traditional, competition scene. Yeah, we don't really have that kind of scene so much in England—at least, not in my experience—but I know it's much more important in Scotland and Ireland. Yeah, it's a big thing. And it's really interesting, because it's in itself a folk tradition, if you know what I mean. But I don't think that it's the folk tradition that it thinks it is. It's a different thing entirely. The idea of performing a bothy ballad in a competition setting is different from performing it in a Bothy. And I think that links a lot to your work in terms of how traditions are formalised. That's grown out of the folk revival, and often eliminates women's contributions to the tradition in a major way. Initially I was really interested in that, about reasserting myself into the tradition as a woman and being like, I have a place here, I can sing these songs. But that led me to thinking not only I can sing these songs, but I can also like, dig backwards and find out where my tradition as a Scottish woman was, taken away from me, and how I can rebuild it. I feel like I’m not the best person to speak on this as I’m kind of less interested in the ‘folk’ that is a reproduction of the canon. We already know that the canon of folk music and dance and customs is exclusionary, it doesn't include women, and it certainly doesn't include anyone who's not white. It’s hardly been updated since the 1950s / 60s and those were not exactly a golden era for representation. I recognise that there is a record store genre called ‘Folk’ which is largely based on that canon—and on a personal level, I grew up with that and I love it so much, BUT for me that’s only a small fraction of what ‘folk’ as a term can be. I’m most excited about ‘folk’ as a word for the culture we create for ourselves, how it empowers us all to be artists and performers, rather than merely consumers, and potentially provides a route to challenge and destabilise dominant culture and politics. I feel like the folk scene can absolutely be a space for that to happen, and it already is in some cases, but those scenes are not the extent of what ‘folk’ might apply to. Something I found interesting about that is I think there can be a tendency to towards, identifying other people as being authentic. Seeing them as from a more ‘primitive’ folk tradition or a more ‘pure’ folk tradition, and then trying to attach to them. And I think that's something that some musicians have done. You know, talking a lot about a relationship with a particular Traveller. As if that then kind of gives you a free rein to do what you want with a tradition because you've kind of been given the go ahead by one person from within that tradition. But its also kind of what I have done in terms of my interest in Lizzie Higgin’s work, even though I have never met her.

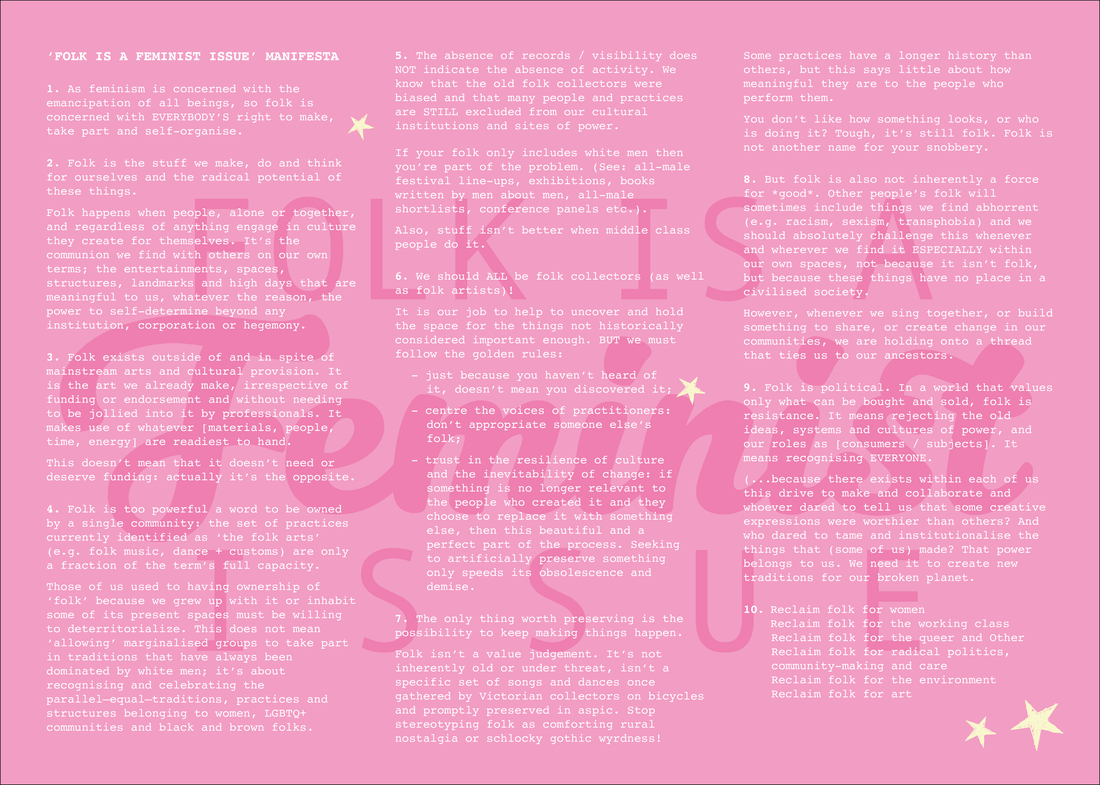

I always feel that for professional folk musicians there's a whole thing around branding and marketing ‘authenticity’ and what that looks like. I think you can have an authentic engagement with a song or repertoire regardless of your background or who you have studied with, but it’s undeniable that certain kinds of self-narration sell better than others, in those High Folk spaces you’ve mentioned, like The Guardian. I think we have to be wary of stories that in themselves reproduce assumptions about folk and rely on outdated beliefs in the primacy of the oral tradition and the existence of a special group of people, proximity to whom can confer status and validity. For me, the most interesting folk practises are the ones that don't call themselves folk at all. As soon as something describes itself as ‘folk’ it tends to accrete a whole lot of assumptions that shape how it is read and practiced. I'm returning to my favourite performance—girls’ carnival morris dancing—because they don't refer to what they do as folk and they don't have any significant connection to the contemporary folk revival. That’s what has enabled that practice to evolve and stay relevant to that community. There’s been less of an emphasis on preservation, and more on catering to the needs of the performers who keep it going. Girls’ morris does have a long and fascinating history, but actually, the performance is very forward facing, it's always renewing, changing every single year. And that's why I think it continues to appeal to such a young demographic. I have this pet theory based on Jacques Derrida’s concept of the ‘marrano’ about folk being ‘a secret that keeps itself’—so that as soon as it becomes too self-aware it kind of loses something, but that’s a difficult thing to pin down, I’m still working on it! It's like the game that you lose when you remember you're playing it…. We have a magazine in Scotland, the Living Tradition. I always say, it is the only magazine I've ever read that opens with obituaries, every issue. The first feature is obituaries. I'm like, wow, this is a bold move. And the letter sections are full of people wondering why they can't get anyone to come to their folk club, or anyone to take over the organising roles of their folk club. And then having tried to get gigs at folk clubs, with a slightly different style to what they are used to, which is actually more similar in style in many ways to the original singers they want to celebrate, and you get rudely rejected. I just thought, oh, well, no wonder, and found opportunities elsewhere to share my work. I was briefly in a band and we did play a lot of folk clubs. And it was one of the things that kind of made me sad because I also wanted to play to my own age group. I mean, we had some absolutely lovely audiences, but I did feel the lack of there being younger people in the crowd, except possibly at some festivals. And I thought, ‘yeah, where are my generation within the folk scene?’ They're out there, for sure, but maybe not so much in those formal settings. Yeah, I think that's it. When you're performing folk music, or any kind of folk ritual or dance or whatever, you're doing it in an effort to connect socially with your community, aren't you? If you're investing in an art form and then going out to perform it and it's not fulfilling that need for connection, that social need, then it either becomes a purely business thing or you just give up. And I think that's that's the thing - there's some kind of disconnect or tension between folk as a practice, process, concept, theory, and folk as a kind of genre of music. The kind of music that will be categorised as folk, with a capital F. The concerns of professional folk musicians are very similar to those of anybody else trying to make a living in music. My rejecting of the aesthetics of folk goes back to this thing of reminding us that folk musicians are ordinary people. And everybody can be a folk practitioner of some kind. I don't want that to be separated from everyday life. Yeah. And I think that is partly why representation in folk is so monocultural and White- because actually, if you're not white, and you're making music, you're immediately classed as not folk. It's a self perpetuating thing.It's not that there are no black people playing folk music, it's that our white community doesn't recognise that music as folk music with a capital F. You talk a bit about this in your manifesta. Can you chat us through that a bit? I've been passionate about the same stuff for about a decade now, and the manifesta is just sort of the latest, hopefully most concise argument that I've put out to date. Some people have asked me, if ‘folk’, as a term, has all of these problems and misunderstandings, why don’t you just use a different word? My view is that ‘folk’ is such a great, powerful word and it deserves rehabilitation and reclamation. In fact, I feel as if we really need some form of ‘folk’ now more than ever! I'd love to see folk cease being viewed as niche and ‘special interest’ and instead come to mean something really powerful and inclusive and radical, because it's the creativity that we already have, as opposed to the creativity that we need outsiders to kind of tell us how to do. I work for an arts institution, and I'm aware of how institutions have come to be the arbiters of what art is what deserves funding and visibility, but what I like about ‘folk’ is that it allows for—and celebrates—all kinds of creativity. And the important thing is just that we are making stuff for ourselves, whatever that is, it's important that we keep doing that, because we live in a world where buying stuff is constantly presented to us as a solution. And I think these opportunities that we have to make stuff whether it's on our own, or with others, are so important. It helps us see the world in a different way, helps us ask questions of those in power and envisage other ways forwards. That's what needs to be protected, that possibility. And that's what I focus on when people ask why I care about ‘folk’ so much. Comments are closed.

|

AuthorWritings, reflections and an archive of research from Quinie (Josie Vallely). Archives

February 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed